FLOATNotes: The Gulag Archipelago

The Gulag Archipelago: Float Book Review

Gratitude and meditation in the face of totalitarian horror.

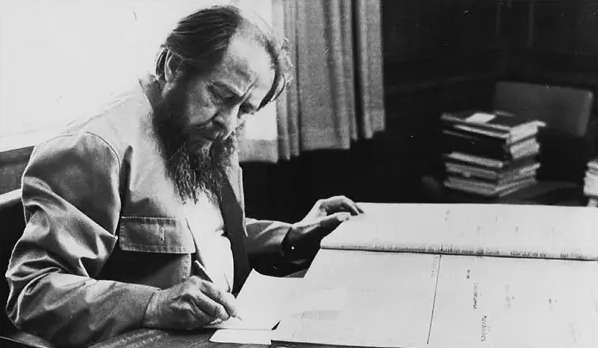

The link between a work of early 20th-century Russian history and float tank therapy may seem dubious, but The Gulag Archipelago by Alexander Solzenitizen is more than a mere record of abuses by Stalin's secret police. The book tells hundreds of stories at once from over 200 contributors, distilling them into the universal experience of Russia during the Gulag years. From arrest to interrogation to holding cells and labor. You'll find demoralizing lists of every torture used, every interrogation tactic, every evil invention on the part of the bluecaps, each with an anecdote and a name of a prisoner who lived to bare witness. I've taken three passages that cut through the horror of recollection as particularly pointed, relevant, or applicable to our first-world experience.

From chapter III, The Interrogation. Solzhenitsyn is telling stories of different prisoners' reactions to their month-long interrogations, where guilt is assumed and the goal is not fact-seeking, but demoralization and control. With this hindsight, he considers what the optimal approach to this abuse would be. The attitude expressed is one that I believe is achieved with meditation and sensory deprivation; radical acceptance and love for the condition of life.

So what is the answer? How can you stand your ground when you are so weak and sensitive to pain, and when people you love are still alive, when you are unprepared?

What do you need to make you stronger than the interrogator and the whole trap?

From the moment you go to prison you must put your cozy past firmly behind you. At the very threshold, you must say to yourself: “My life is over, a little early to be sure, but there’s nothing to be done about it. I shall never return to freedom. I am condemned to die- now or a little later. But later on, in truth, it will be even harder, and so the sooner the better. I no longer have any property whatsoever. For me those I live have died, and for them I have died. From today on, my body is useless and alien to me. Only my spirit and my conscience remain precious and important to me.”

I have been listening to and following along in my copy of The Gulag Archipelago from our library in Greenlake. The feelings that you get reacting to the endless and varied accounts of abuse are those of pity, despair, and gratitude. I would have included disbelief if I had not already been exposed to the better-known brutality of wartime Germany or present-day North Korea. Evil is rarely new, but it is always fresh.

Pity and despair of course. But gratitude for the love and comforts I've done nothing to deserve except to have been born into another system. Gratitude for how my suffering during a three-minute ice bath is temporary and at will. How my labor is compensated, and my problems are ones of having nice things that need upkeep or choosing what foods will keep me healthiest.

But why must we feel gratitude? Because we are as capable of these evils as anyone who's ever lived. Solzhenitsyn pegs ideology as the reason for evil on this scale- and ideology is something we all are susceptible to. Read his description of ideology as the rationalization responsible for the worst evils.

"The imagination and the spiritual strength of Shakespeare’s evildoers stopped short at a dozen corpses. Because they had no ideology. Ideology is what gives evil doing its long-sought justification and gives the evildoer the necessary steadfastness and determination. That is the social theory which helps to make his acts seem good instead of bad in his own and others’ eyes so that he won’t hear reproaches and curses but will receive praise and honors. That was how the agents of the Inquisition fortified their wills: by invoking Christianity; the conquerors of foreign lands, by extolling the grandeur of their motherland; the colonizers, by civilization; the Nazis, by race; and the Jacobins (early and late), by equality, brotherhood, and the happiness of future generations.”

Sensory deprivation rests on at least one axiom- that the end is the means. When put into an environment where there appears to be nothing at all, you find peace. There is no place for ideology in sensory deprivation; no greater good or goal than peace and gratitude.

There were never trials against commanders, officers and camp guards like there were after WWII, and there is immense power in the hours of records in its entirety, as compiled by a prisoner lamenting a justice that will never be achieved. When talking to an elder that Solzhenitsyn shared time in a cell with, the man said something to him, the weight of which didn't hit him until much later. I believe The Gulag Archipelago is like this- and deserves to be read and reread to absorb the weight of every man's capacity for evil, the danger of ideology, and gratitude for peacetime and the presumption of innocence. Here is that passage. It begins with dialogue between him and his cellmate.

“...all the hard labor politics have been destroyed, and they even dissolved our society in the thirties.”

“why?” I asked.

“So we would not get together and discuss things.”

And although these simple words, spoken in a calm tone, should have been shouted to the heavens, should have shattered window panes, I understood them only as indicating one more of Stalin's evil deeds. It was a troublesome fact, but without roots. One thing is absolutely definite: not everything that enters our ears penetrates our consciousness. Anything too far out of tune with our attitude is lost, either in the ears themselves or somewhere beyond, but it is lost."

And why then, do not our voices shout to the heavens and shatter window pains, that all a person needs is to spend time with themselves to find happiness! Would it be heard? Or too far out of tune with the cultural attitude. Mediation is the key to peace in one's heart, the prerequisite to peace in the family, nation, and home. Sensory deprivation brings deep meditation to the masses!

Read works of history as a mirror to the good and the evil in your community, and meditate on the words and the images they create as you would meditate on a thought in a float tank. This is the path to peace in our time. You can check out The Gulag Archipelago at our float library in GreenLake.